In July 2025, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins publicly warned that individuals and companies with ties to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were actively purchasing farmland near US military bases, posing a serious national security threat. The US Department of the Treasury swiftly expanded its foreign direct investment review framework to cover 227 sites near 56 military installations across 30 states, aiming to prevent such acquisitions from becoming channels for intelligence infiltration. As of early 2020, Chinese controlled farmland in the US exceeded 190,000 acres, with an estimated value of nearly $1.9 billion. Some of these parcels are located close to sensitive facilities involved in biowarfare, weapons development, and military communications such as the Dugway Proving Ground in Utah.

At the same time, Israel’s Ministry of Defense voiced security concerns about Chinese automaker BYD, citing the risks associated with its vehicles’ built-in sensors, cameras, and vehicle to everything technologies. These systems collect not only driving behavior and location data but also potentially sensitive information surrounding government buildings and military installations. Under China’s National Intelligence Law, all companies are obligated to cooperate with state intelligence agencies. Even without direct evidence of espionage, I believe the systemic risk is simply too large to ignore.

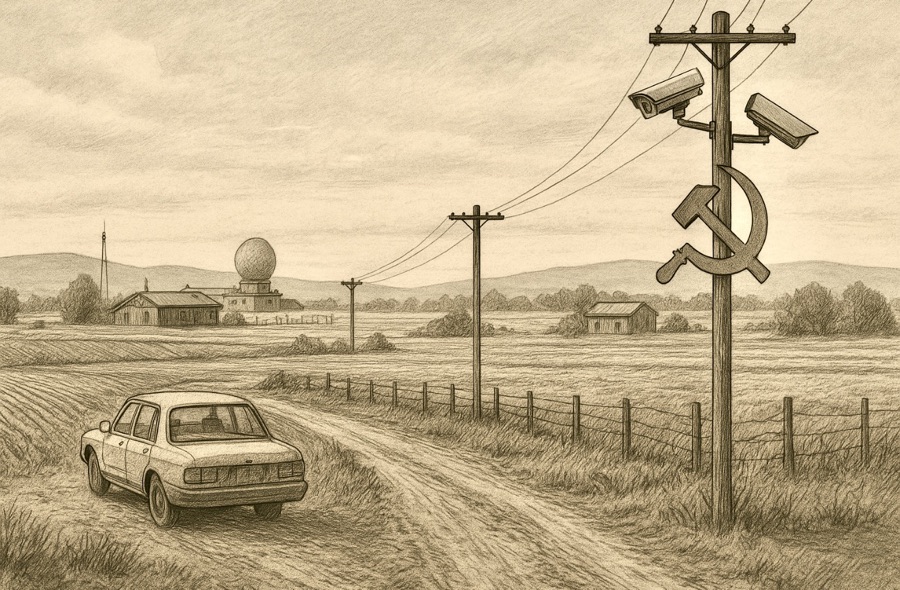

To me, these seemingly isolated incidents reveal a broader, more strategic power logic: authoritarian regimes are using the openness of global markets and the ubiquity of modern technology to conduct silent infiltration and control. They are turning commercial activity into a strategic tool, integrating information collection and economic positioning into a new form of warfare.

The Authoritarian Logic Behind China’s Technological Upgrades

Historically, the CCP’s governing tactics have closely mirrored those of the Soviet Union placing intelligence at the core of regime stability, treating personal privacy as a threat, and viewing social mobility as a source of instability. While the KGB relied primarily on human infiltration and bureaucratic surveillance, the CCP has scaled these mechanisms through digital technology in the 21st century. Today, facial recognition, social credit scoring, voice pattern analysis, digital identities, and big data surveillance are not occasional practices, but the normalized backbone of a national surveillance apparatus. China’s “Skynet Project” reportedly oversees over 600 million surveillance cameras, equivalent to one for every two citizens.

To me, this is not merely technological advancement. it is the systematic dismantling and reconstruction of individual liberty through engineering. The CCP doesn’t just own the surveillance infrastructure; it also controls the narrative that legitimizes it. Algorithms have replaced police patrols. Predictive analytics have become policy enforcement tools. Repression has been recoded as “stability maintenance.”

More crucially, the logic behind this domestic control system is being exported, not through overt political ideology, but through commercial investment, infrastructure projects, and technology exports. For instance, smart city infrastructure projects under the Belt and Road Initiative are often built by Huawei and ZTE, allowing for remote management and data integration with China. I increasingly feel that sectors like connected vehicles, agricultural land, and smart grids are being strategically absorbed into China’s state-driven tech ambitions.

This is what I see as a form of “invisible geopolitical warfare.” Unlike traditional conflicts waged with tanks and missiles, today’s confrontations are waged through market transactions and technological infrastructure. Ironically, the free-market systems we cherish have become the perfect stage for authoritarian regimes to wage soft power wars, subtle, silent, and structurally embedded.

Europe’s Liberal Ideals and Institutional Vulnerability

Frankly, I find Europe’s posture in this emerging tech-geopolitical conflict deeply concerning. The European Union has long upheld privacy, freedom, and human rights as its core values which I respect, but these ideals have also fostered institutional vulnerabilities in the face of authoritarian infiltration. Many European nations, out of an instinctive aversion to the word “surveillance,” have hesitated to deploy protective technologies in critical spaces such as hospitals, schools, and government agencies. In my view, this reflects a dangerous moral confusion. we are afraid of becoming like our adversaries, so we choose to remain defenseless.

When we refuse to adopt protective measures simply because they “sound like something China would do,” we are allowing a dangerous form of moral purism to undermine our own resilience. I feel like we are fighting a highly coordinated authoritarian threat with ethical restraint rather than institutional preparedness.

Even more troubling is Europe’s fading sensitivity to the cultural and historical logic of authoritarianism. Compared to the Cold War-era vigilance against the Soviet Union, today’s European stance on China feels divided, hesitant, and tainted by economic self-interest. If an entire regime treats land, technology, people, and companies as extensions of the state, then what are we really engaging in when we call it “free trade”? Aren’t we, in effect, handing over our democratic values as exploitable vulnerabilities?

Freedom Requires Both Institutional and Cultural Defense

The free market itself is not the problem. What’s problematic is our blindness to its vulnerabilities and our lax institutional safeguards. When authoritarian regimes consciously militarize market behavior while we continue to boast about “openness,” we end up paying the price for our own ideological complacency.

The solution, in my opinion, goes far beyond tightening investment reviews or enhancing cybersecurity. What we truly need is a cultural and moral awakening. We need to strengthen education systems to teach the history and logic of authoritarian control and to build long-term institutional resistance. As the World Values Survey (WVS) has shown, a society’s approach to individual liberty and state power deeply shapes its institutional structures. That is the battleground where democratic nations must hold their ground.

I firmly believe that freedom is not a default setting. it is a fragile construct that must be consciously chosen and vigilantly maintained. In this bloodless war, if we fail to recognize the authoritarian encroachment embedded within our own systems, we may one day wake up to find that “freedom” has become little more than a footnote in our historical documents.